Some context before we start…

We may agree that VeriSign runs one of the best business models in the world. Imagine owning the exclusiveness for managing and renting a highly demanded product which is paid upfront each year on a subscription basis, results critical to the operations and branding power of most companies around the globe and whose price (relative to the service covered) is ridiculously low.

Such wonderful unit-economics are at play in VeriSign’s activities, where the domain names using its .com extension -or any other, for that matter- cannot be outrightly purchased but only rented for pre-defined time frames.

The .com extension (standing for commercial) was created as one of the first TLDs (Top-Level Domains) when the DNS (Domain Name System) was introduced, aiming to host the commercial side of a business on the internet (there are rumours about different origins but we will skip them on this entry).

Since then, the .com TLD has become the de-facto standard and is nowadays at the epicenter of the digital revolution (accounting for roughly 37.0% of all domains worldwide as of writing this, or around 245.0 million total registrations).

Every extension is managed by a registry operator in exclusiveness. The degree of complexity which arises if multiple organizations are entitled to handle (create, delete, control leasing contracts, monitor payments and renewals from lessees, etc.) domain names under the umbrella of a given TLD makes the task almost impossible, as each domain name must be unique within a given extension.

As a consequence, the regulator of the industry -ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers)- designates and certifies specific companies to be the unique registry service providers of any given TLD.

VeriSign happens to be the registry not only of the .com extension, but also others like .net -which as of April 2023 hosts 3.2% of the total registered domains (or 21.3 million)-, .cc and .name.

Within the industry, there are (mainly) two broad groups of TLDs: gTLDs (generic TLDs) and ccTLDs (country-code TLDs). The former group gathers generic-purpose extensions such as .com, .net, .org or .gov, whereas the latter contains country-specific extensions like .us, .uk, .nl, .es or .au. It is precisely a sub-set of the first type of TLDs (gTLDs) where CentralNic’s story begins.

Starting in January 2014, ICANN kicked off the New gTLD Program with the goal of enabling the largest expansion of domain names to date by fostering “the biggest change since the internet’s inception”. This program consisted of sequentially rolling out new generic domain extensions, and more than 1200 ngTLDs (new generic TLDs) have been released in the subsequent 8 years.

From these, the 10 whose use has spread the most are .xyz, .top, .info, .icu, .online, .site, .club, .biz, .shop and .loan (the extensions in bold have CentralNic as its sole backend, similarly to what VeriSign is to the .com and the .net TLDs).

If none of the ngTLDs listed sounds familiar, I recommend you visit the following website and check its extension!

If you are hesitant to click on an external link:

The website above is Alphabet’s (Google’s parent company) investor relations page, indexed under the .xyz TLD.

Even though the activities described in the introductory paragraphs only account for one half of the business, I believe we are now equipped to jump into CentralNic’s specifics.

i. Business overview.

Founded in 1996 and headquartered in London, CentralNic was listed on the AIM (Alternative Investment Market) section of the LSE (London Stock Exchange) in 2013. Despite compounding sales at an annualized pace of 86.6% (I have not misplaced the decimal separator) since its IPO, CentralNic -with an enterprise value of c.£390.0M as of April 2023- can still be considered a relatively small company whose operations focus on two areas: Online Presence and Online Marketing.

This impressive growth rate has been mostly achieved via acquisitions and, I shall add, at the expense of shareholder dilution (starting with 58.1M shares outstanding in FY2013 and ending FY2022 with a pool of 268.2M shares) and issuance of bonds, which results striking in view of the highly cash generative nature of the business. This may provide an idea of how aggressive the management team has been in the past in pursuing market-share gains. We will revisit this topic later.

i.i. Online Presence.

The introduction we have gone through only refers to the environment surrounding the Online Presence segment, which comprises all services related to the domain names industry.

What CentralNic does in this segment is, primarily, handling the registration, renewals and associated services to the domain names (websites, e-mail addresses, etc.) of its customers, whose size ranges from large corporations to SMEs. In any case, revenues derived from the management of domain names under specific TLDs present a high degree of stickiness (around 98.0% of customers renew their domain leasing contracts every year) and strong visibility (it is not possible for a customer to outrightly purchase a domain name, so the only path to maintaining the rights over it is by renewing the leasing contract on a yearly basis, which implies the execution of the binding payments upfront).

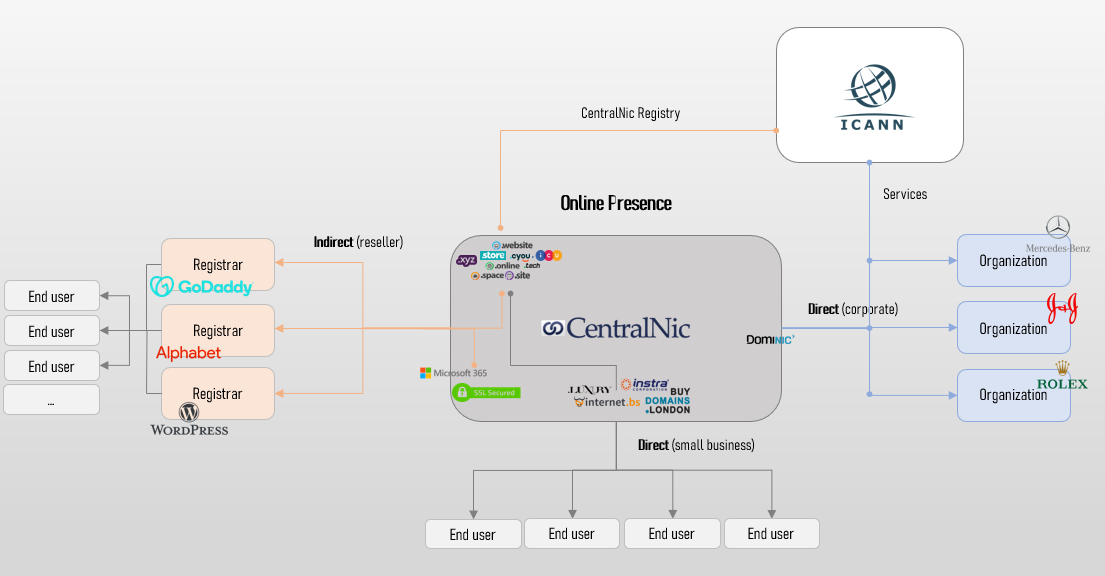

I have comprised, to the best of my knowledge, how the Online Presence segment works for CentralNic in the picture below:

We can establish two main operating areas within the segment: Direct and Indirect.

Direct:

This area receives its name from the nature of the relationship between CentralNic and the customer. Within this group, CentralNic’s clients are the end users of the domain names that are being registered or the direct beneficiaries of the services provided. In other words, CentralNic is handling the domain names and related services for entities with whom the company maintains a relationship without any intermediary.

The strategic approach that a customer may take in relation to its domain name(s) on the internet varies widely based on the total size of the enterprise: while for small and medium businesses (bottom part of the image above) it is a matter of guaranteeing their online presence and ensuring that their businesses are easily discoverable on the internet, large corporations (right side of the picture) view domain names as a form of intellectual property and tend to demand more complementary services such as filing for their own SLDs (Second Level Domains) with ICANN or securing a portfolio of domain names containing all addresses which the customer considers may be required in the future (in this case CentralNic takes care of the complete management of such portfolios).Some examples may help in understanding how these services play out:

SMEs:

Let’s imagine a small business selling videogames in physical stores whose name is GameStore.

GameStore realizes that providing videogames via digital channels will prove to be key for the future of the industry and decides to open a website to complete this transition on a timely manner.

GameStore then reaches out to CentralNic and checks if the domain name gamestore under the .xyz extension is already taken. Luckily for them it is not, so GameStore decides to block this name from competitors and opens a leasing contract with CentralNic, who will take care of (i) registering the domain name entry on the .xyz registry and (ii) manage all maintenance and administrative activities required as long as GameStore continues to use the website www.gamestore.xyz.Large corporations:

Now let’s image that GameStore is not a SME but a large and well established business. GameStore is more focused on keeping competition at bay and ensuring that no other player in the industry takes away a domain name that could potentially be needed in the future so, instead of registering a unique address like www.gamestore.xyz, it asks CentralNic to create and handle a portfolio containing 50 domain names (gamestore.xyz, gamestore-customersupport.xyz, gamestore-news.xyz or gamestore-investors.xyz could be some of them).

Or, even further, GameStore could be interested in having its own extension indexed under the .xyz TLD (for instance .gstore.xyz). In this case, CentralNic’s services would help GameStore in completing the request and filing process with the industry regulator (ICANN). After achieving its own extension, GameStore has effectively committed to pay CentralNic for keeping its own SLD (.gstore) under one of CentralNic’s registered TLDs (.xyz). Additionally, GameStore could now be even more interested in having a portfolio of domain names on its own SLD (again, examples of these could be customersupport.gstore.xyz, news.gstore.xyz or investors.gstore.xyz), and it would be more convenient to let CentralNic handle the management for every domain name on it as well.

Indirect:

In this case CentralNic’s customers are not the final users of the domain names they are registering, but (typically) large enterprises which provide fees and comissions to CentralNic for the registration requests that they are filing on behalf of their customers (see the left side of the picture above). Such businesses are often referred to as registrars and the contracts binding them to CentralNic (registry) are of a revenue-shared nature.

While CentralNic’s role in the Direct segment can be seen as a retailer, this role shifts towards wholesale activities in the Indirect space.

i.ii. Online Marketing.

Historically, the Online Presence segment accounted for all the sales generated by the company. It is only at the end of FY2019 when, after the acquisition of Team Internet, CentralNic begins its Online Marketing operations.

Due to its relative degree of novelty, this segment is often misunderstood by investors. Keeping things simple, we can see CentralNic as a pure play in the digital advertising space with a special focus on offering value-added services to both online consumers and advertisers. The way CentralNic approaches this is by acting as an intermediary between both parties.

Again, the picture below resembles the mental model I have used in an attempt to understand the business dynamics behind this segment:

CentralNic is first approached by merchants that desire to increase the presence of their products and/or services in the market. After the corresponding binding contracts -usually in the form of revenue-shared or fee-for-service agreements- are signed by both parties, the three steps gathered in the schematic above describe how the logical path for a potential online consumer looks like.

A specific example has been set where the online consumer is actively looking for a coffee machine for his/her home.

CentralNic first places broad-topic advertisements across the main social media platforms (Facebook, Instagram and TikTok, among others), search engines and publisher websites which do not relate to any specific merchant. When the online consumer runs into one of CentralNic’s advertisements, he/she may be surfing the web for other purposes or specifically seeking information on the relevant topic (in this case coffee machines).

After the online consumer accesses one of CentralNic’s posts, he/she is redirected to a website where useful and educational information is presented. This information in the form of merchandise reviews, relevant characteristics of the product range and, most importantly, a comparison and ranking list of models from different merchants (which have active contracts with CentralNic) within that product space. These rankings are sortered according to useful metrics for the consumer, such as best price-quality relationship, cheapest item, highest quality, etc.

In our example above, four models of coffee machines are presented, each belonging to a different merchant (CentralNic’s customer): Amazon, Nespresso, Philips and De’Longui.

If the online customer proceeds and clicks on one of the options being presented, he/she is taken to the specific merchant’s website and CentralNic collects a fee from the advertiser. Furthermore, should the online consumer end up purchasing the good at the merchant’s website, CentralNic would then collect an additional commission.

In my view, although the Online Marketing space provides CentralNic with recurring revenues, these are less predictable and more cyclical than the sales generated by the Online Presence segment.

We will address the unit-economics and what are the main implications behind both business models -as well as their KPIs- in the Thoughts. Qualitative analysis chapter.

ii. Sector.

Following the same approach as drawn in the previous chapter, we can study the two sectors corresponding to the Online Presence and Online Marketing operations.

ii.i. Online Presence.

With a TAM (Total Addressable Market) estimated around US$30.0 billion and an industry average growth rate of c.3.0%, the Online Presence segment is the provider of CentralNic’s highest quality revenues (strong visibility) and also the most mature one, so it is reasonable to expect lower organic growth rates than in the Online Marketing space.

In my view, studying the macro-trend among different types of TLDs (ngTLDs, gTLDs and ccTLDs) results as important as investigating how CentralNic is positioned, within the ngTLD space, to benefit from industry tailwinds.

As of April 2023, ngTLDs (where CentralNic operates) have reached 115.0M registrations worldwide -representing 17.4% of total domain names-, whereas gTLDs and ccTLDs contain 283.3M (42.7%) and 264.6M (39.9%) of the active domain names on the internet.

We observe a rapid increase in the amount of new registrations being created since the pandemic which, as of writing this, has not started to ease. In order to mitigate being fooled by short-time effects, let’s see the different growth rates for each of the aforementioned TLD categories both before and after the pandemic.

From 2013 (when ICANN started rolling out the ngTLDs) through 2020, the total amount of domain names registered under ngTLD extensions increased at a CAGR of 24.5% (from 2.0M to 9.2M). Since the start of the pandemic, the annualised growth rate has accelerated to a staggering 131.98%, ballooning from 9.2M to 115.0M as of April 2023.

Comparing this with its peer groups, gTLD and ccTLD registrations increased at an annualised pace of 13.97% and 14.24% (respectively) over the 7-year period ending in 2020 and, since then, at a CAGR of 40.2% and 78.9%, respectively.

From these numbers we can make three observations since ICANN started the New gTLD Program in 2013: (i) the pandemic forced many businesses around the world to strengthen their digital footprint, resulting in higher growth rates of new domain names since 2020, (ii) the amount of ngTLD registrations is increasing faster than any other type of TLD and (iii) this differential growth pace is broadening and accelerating in recent years.

How well has CentralNic positioned itself to benefit from the industry tailwinds that the ngTLD market is experiencing both in absolute and relative terms when compared to other TLD categories?

From the 115.0M ngTLD existing domain names in April 2023, CentralNic owns the exclusiveness as the registry provider over 42.4M registrations (or 36.9% market share within the ngTLD space), far ahead from its closest registry competitors (GoDaddy Registry and Identity Digital, with 10.9% and 3.3% market share, respectively).

If we shift the approach to an individual-TLD analysis, we find that CentralNic is the unique registry provider for 4 out of the top 10 most used ngTLDs worldwide. As we will see in Thoughts. Qualitative Analysis chapter, the sector is characterised by strong network effects which create a winner-takes-all environment where the most spread and common extensions result more appealing to new potential users. It is therefore no surprise to see that the top 10 most used ngTLDs account for 64.7M registrations, or 56.3% of total domain names worldwide under ngTLD extensions.

It is probably worth remembering that there are, as of the time of this writing, 1254 ngTLD extensions available, so 0.8% of ngTLDs (top 10) contain 56.3% of the domains (115.0M).

During the assessment of the possible outcomes for the contribution of this segment to CentralNic’s valuation (Valuation chapter) we will use the TDR (Total Domain Registrations) and the ARPD (Average Revenue Per Domain) as key indicators.

ii.ii. Online Marketing.

The Online Marketing segment (monetisation of internet traffic) is estimated to have a TAM of c.US$400.0 billion. Currently experiencing a rapid expansion (around 21.6% increase in 2022 when compared to the previous year) and expected to continue at a CAGR of 14.3% through 2028.

CentralNic’s operations in the Online Marketing space begin with the acquisition of Team Internet in December 2019, which facilitated a strategic expansion into the monetisation of internet traffic by integrating the ZeroPark platform into the company’s operations.

CentralNic acquired Team Internet for a total consideration of US$48.0M, of which US$45.0M were paid in cash (via bond issuance of US$40.0M with a maturity of 4 years and a coupon of three-month EURIBOR plus 7.0% p.a.) and US$3.0M in shares. On a pro-forma basis, this represented around 3.5 times EBITDA.

This acquisition proved to be transformational for the company, as the Online Marketing contributes, as of FY2022, US$574.7M (or 78.9%) to total sales.

During the assessment of the possible outcomes for the contribution of this segment to CentralNic’s valuation (Valuation chapter) we will use the TVS (Total Visitor Sessions) and RPTI (Revenue Per Thousand Impressions) as key indicators.

iii. Financials.

For the full FY2022, the weight contribution to total revenues of the group by each of its reported segments was as follows: (i) 21.1% (US$153.5M) were generated by the Online Presence activities, growing 2.8% year-over-year and (ii) the remaining 78.9% (US$574.7M) came from Online Marketing operations, growing 120.0% compared to the full FY2021 (of which 86.0% was organic).

As a whole, CentralNic grew its top-line 77.4% in FY2022 (c.60.0% organically), mainly driven by its Online Marketing segment.

Since IPO-ing in FY2013, CentralNic has increased total revenues at a more than impressive 87.0% CAGR primarily due to an aggressive M&A strategy, averaging 3-4 acquisitions per year and doubling sales in 4 out of the last 9 years.

Derived from its M&A activities and following accrual principles, large amortisation charges are computed into the P&L every year which make the company report net losses in most periods. This, together with the massive share dilution to which existing shareholders have been exposed to during the past decade makes the company difficult to screen.

Nonetheless, the highly cash generative nature of the business materialises when we look at its cash-flows. In FY2022 alone, reported amortisation charges amounted to US$36.4M which, added to the US$14.8M of NPAT (last year has been one of the exceptions where the company reported positive bottom-line) and adjusting for changes in working capital (payables tend to increase faster than receivables) result in US$71.8M net cash from operating activities (roughly 5 times higher than reported NPAT).

This relationship between reported income according to accrual principles and actual cash-flows holds true in previous years as well, and will continue to be the case as long as management continues to prioritise M&A activities over organic investments. Even though US$81.5M were spent in acquisitions during the year, we will see in Management and Thoughts. Qualitative analysis chapters why we may be at the doors of a shift in management’s priorities with the recent appointment of Michael Riedl as CEO (previously CFO of the group since 2019).

The amount of debt issued by CentralNic in recent years in order to fund its M&A strategy has reached a point where, if it would not be by the terrific cash generative nature of the business, I doubt the company would continue to exist nowadays. The most critical point happened during the period FY2019-FY2020, where interest coverage was around 1.5 times which, in my view, it is not acceptable given the quality of the business model that CentralNic has.

Since then, the situation has improved to a more reasonable (although still somewhat weak) 3.7 times interest coverage.

As of FY2022-end, the company had US$151.2M in borrowings (of which US$5.3M are payable within FY2023) and cash deposits of US$94.8M, so with total net debt of US$56.4M and FCF of 70.4M, CentralNic is in a position where it could pay down its entire debt in a little more than two years without touching its cash and equivalents, or less than a year by using it.

Most of these borrowings were refinanced during FY2022 with maturity dates of October 2026 (with an option to extend by a further year) and bearing a cost of 2.75% above SOFR (Secured Overnight Financing Rate) -roughly 7.0% at current rates-.

Due to the maximum amount of characters which are permitted per e-mail, I am forced to split this entry in two parts.

In part II, the following topics will be addressed: management, thoughts and valuation.

revenue growing only with acquisitions, never profitable, what's the catalyst?

Nothing said about margins?